Then + Now: Short Takes by UCLA Historians in the Age of Corona

The Luskin Center for History and Policy and the UCLA Department of History are pleased to announce a series of short and diverse reflections by historians on the current COVID-19 crisis. The following “short takes” offer interesting historical perspective on the present-day pandemic.

Make sure to keep coming back for new posts.

Responding to Crisis with "Fasting and Prayer" by Carla Pestana

Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards

On July 16th, the Governor of Louisiana called for three days of prayer and fasting to combat the spread of coronavirus. John Bel Edwards’ call followed a lackluster government effort to combat the virus, a predictable surge in cases, and a belated order mandating mask wearing

The governor’s call for fasting and prayer to counteract a global pandemic has a decided seventeenth century ring to it: colonial American governors occasionally called for such days in response to community hardship. A devastating fire or a poor harvest might elicit a day of prayer. On such a day, the community would gather to express contrition for its sins, in the hopes that God would stop its suffering. The logic that bad news followed bad behavior was called providentialism: God punished or rewarded, and the community hoped to determine what it had done wrong (or right) in order to avoid punishment and deserve reward. This logic is at play again in Edwards’ response to COVID-19.

Colonial Americans, however, would have advice for Edwards: don’t simply pray and fast, also act. They believed God called them to do what they could to achieve a good outcome. No one would pray for a good harvest if they had not planted a crop, in other words. Hence the governor’s foot dragging on basic measures that would slow the virus’s spread would have rendered his call for prayer highly problematic, in the eyes of his colonial predecessors, and, they would have thought, in God’s eyes as well.

Covid-19 and the lessons from history by Soraya de Chadarevian

Since the World Health Organization defined the Covid-19 crisis a pandemic, innumerable comparisons have been drawn to earlier such events.

A favorite has been the influenza pandemic of 1918-19, but also earlier plague pandemics and other more recent events like the HIV/AIDS, H1N1 and SARS pandemics are frequently cited. Historians of medicine have been queried about the lessons that can be learnt from these earlier events and what might be predicted about how the current pandemic might end—a question that is still very much in search of an answer.

But what exactly can we learn from history? For sure, historians studying earlier pandemics have detailed knowledge of the deep social and economic disruptions and complexities of such events. They see how narratives are formed, which views come to dominate and which voices are silenced. In short, they are able to ask pertinent questions and compare.

Yet historians also know that no two historical events are the same. Looking back then can help highlight the specificities of the current situation and its historical underpinnings—and this may be exactly what we can learn from history. Indeed, the Covid-19 virus appears like a lens that makes the peculiarities, tensions and contradictions of our time glaringly visible as we are currently experiencing them. These experiences will be different depending on where we live and where we stand. To collect this multitude of voices and ensure they become part of the narrative may be the most important contribution historians can make in this current crisis.

"Boccaccio and the Black Death" By Teo Ruiz

Boccaccio and the Black Death

By Teo Ruiz

Doktor Schnabel von Rom, engraving by Paul Fürst (after J Columbina), Rome 1656. A medical doctor equipped for visiting patients afflicted with the plague: a waxed long cloak, face covered with a mask, eyes secured behind crystal, and pleasantly smelling spices are placed in the long beak.

Epidemics and pandemics before Covid-19 have provided inflection points in world history and culture. The onslaught of the Black Death (black, because of the skin color at critical moments in the illness’ development) in 1348-50 has had a long grip on the European imaginary, mostly because of Boccaccio’s vivid description of the pestilence’s impact on Florence in his preface to the Decameron. Traveling from east to west along commercial roads linking Asia to the Mediterranean, the plague arrived in Italy in 1348.

Moving swiftly throughout Europe, it killed between one third and one half of the population, returning every generation until the 18th century. As Boccaccio tells us, not unlike responses to Covid-19 today, some in Florence heroically stood by the sick, tended to them, buried the dead, and, then died themselves from contagion. The wealthy often fled to the safety of their country villas, as Boccaccio’s characters did. Others, seeing the plague as God’s punishment, went on processions, masses, and the like. They also died. Some people, knowing that death was at hand, embraced pleasure. As is the case today, some of those in power (certainly in the US) proved to be incapable of facing the crisis, So too the poor and those living in crowded cities died in greater proportion than the rich. As Covid-19 will do, the 1348-50 plague led to new social and economic structures, new art forms, morbid religious practices, and changed social relations. As in Europe after 1350, the world emerging today will be different. We should make sure that it is a more humane and just world.

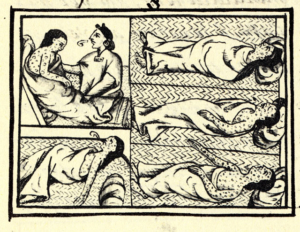

Early American Epidemic Disease By Carla Pestana

Early American Epidemic Disease

Early Americans knew epidemic disease could travel and decimate. Many illnesses were place specific, caused by environmental conditions, making places like the tropics more prone to disease. They did not have a notion of disease vectors, so they found it odd but irrefutable that some epidemics moved, endangering new populations. As recently as 1665-66, the plague had cut down numerous Londoners. Smallpox similarly traveled through Native American populations, brought—we now understand—by Europeans who carried the disease to those who had no immunities.

Early Americans knew epidemic disease could travel and decimate. Many illnesses were place specific, caused by environmental conditions, making places like the tropics more prone to disease. They did not have a notion of disease vectors, so they found it odd but irrefutable that some epidemics moved, endangering new populations. As recently as 1665-66, the plague had cut down numerous Londoners. Smallpox similarly traveled through Native American populations, brought—we now understand—by Europeans who carried the disease to those who had no immunities.

Diseases might move over long distances on sailing ships. Port cities were especially vulnerable to epidemic carried across oceans. Wary town residents watched for news of diseases in distant ports—and the few newspapers invariably contained accounts of distant epidemics that might travel to their own shores.

Like the cruise ships of today, sailing ships of yore could become infected, endangering communities where they disembarked. In this way, yellow fever came to Philadelphia in 1793. A mosquito-borne illness that usually plagued warmer climates, yellow fever escaped ships from the Caribbean at a time of year when Philadelphia was warm enough to host the mosquitos and therefore the disease. A tenth of the city’s population perished, the wealthier residents fleeing for the relative safety of the countryside. Today in our more interconnected world, epidemic can travel further and faster, but fears of migrating diseases are longstanding.

Plague, Pestilence, and Influenza in India: 1897-1920 by Vinay Lal

Plague, Pestilence, and Influenza in India: 1897-1920

By Vinay Lal

The so-called Spanish Influenza of 1918-20 has until recently been known as the “Forgotten Pandemic”, all the more surprising in that the initial estimate by demographers of a massive death toll of around 22 million has steadily been revised to the now commonly accepted and still more staggering figure of a mortality of some 50-100 million. Rather puzzlingly, historical scholarship barely broaches the subject of the course of the influenza in India. No country suffered as much as India: 15-18 million people are thought to have been felled by the pandemic, twice as many as were killed in any other country. The few accounts that we have point to streets littered with corpses and droves of people moving from one house to another in the search of food.

Disinfecting Trans-Lyari plague sufferers in wooden tubs, Karachi, India. Photograph, 1897. Contained in an album of photographs which show the work of the Karachi Plague Committee in 1897. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

Though one might be tempted to suppose that the colonial state had abdicated its duties of furnishing at least a rudimentary public health infrastructure, the picture is rather more complex. From 1897-1908, India was struck by bubonic plague. Here, too, the death toll was immense, something on the order of about 12 million; however, in contrast to 1918-20, the plague is extremely well-documented. The Indian Plague Commission of 1898-99 issued a voluminous report in multiple volumes, and over the course of a decade colonial officials were diligent in documenting the plague’s inroads into nearly all parts of the far-flung British possessions in South Asia. There is also a surprisingly ample visual record, much of it designed to impress the public of the state’s concern for its colonized subjects. In an attempt to ensure that infected patients were not being shielded at their homes by families that were reluctant to visit hospitals, officials attached to the office of the plague commissioner barged into Indian homes. These aggressive intrusions into Indian society were seen by many Indians as evidence of the increasing encroachment of the state on private life. In 1897, in what was one of the first such acts of the political assassination of a colonial official, Plague Commissioner Walter Rand was shot dead by the Chapekar Brothers in Pune.

The “influenza pandemic” of 1918 arrived on India’s shores as the “Great War” was drawing to a close. It may be that the war years, accompanied by food shortages, inflation, labor unrest, and armed anti-colonial activity, had already inured people to suffering. Indeed, as the scholar Ira Klein was to suggest in an article on “Death in India, 1871-1921”, those fifty years were a period of unprecedented calamity for Indians. Besides the bubonic plague of 1897-1908, upwards of fifteen million Indians were killed in famines; and then there were the multiple scourges of cholera, malaria, and smallpox, with a similar tally of the dead. Might we argue that what historians have characterized as the “pandemic” of 1918-20 was experienced by most Indians as much less than that—as just another chapter in the sordid saga of death, and one scarcely worth recording?

What Past Pandemics Predict by Stephen Aron

What Past Pandemics Predict

By Stephen Aron

Pandemics, it seems, invite prognostications. Pundits now fill the airwaves and op-ed pages with predictions about how things will change in the wake of Covid-19. Even after social distancing fades, futurists prophesize profound transformations in how we will work and live with handshakes and hugs held at bay and restaurants and retail shops reduced. So, too, as more people will continue to work from home, freeways will be freed, air cleared, and urban real estate remade. Optimistic progressive visionaries hope for changes that diminish inequities, while pessimists fear that was has been exposed during this pandemic will be exacerbated in its aftermath.

Influenza epidemic in United States. St. Louis, Missouri, Red Cross Motor Corps on duty, October 1918. (National Archives)

What about historians? What predictions might we make based on observations about the past? Certainly, reading the “Then and Now” commentaries offered by my colleagues, we can see the case for the shattering impact that pandemics have had on human societies across the ages and the ways in which they ushered social, cultural, economic, and political changes scarcely imagined before various diseases took their tolls. My own field of study, the history of the North American frontier and West, can’t be understood without reckoning with the calamitous decline of Indian populations that followed the spread of “Old World” pathogens into the “New World.”

Still, I would introduce a note of caution about forecasting far-reaching and enduring changes based on the record from past pandemics. By way of example, I point to the Flu Pandemic of 1918-1919, to which the current Covid-19 outbreak is most often now compared. Historians have of late become much more attentive to what was called “the Spanish Flu,” examining anew its spread and devastation and scrutinizing how different policies in different places succeeded and failed in limiting deaths and rebounding economies.

Yet, when I skim through history textbooks (all of which were written and published before Covid-19 arrived on the scene), I’m struck by how little attention the pandemic of 1918-1919 receives in them. Yes, some textbooks take note of the event’s ghastly death toll (much greater on a per capita basis than almost all predictions about Covid-19’s ultimate lethality). But in U.S. history textbooks, the account never runs to more than a few sentences, a paragraph at most. And once the pandemic had run its course by June of 1919, it disappears, at least as far textbook histories are concerned. In turning quickly to the “Roaring Twenties,” none of the textbooks connects any of that decade’s major developments back to the pandemic that immediately preceded it. That’s true in world history textbooks too. Indeed, I’m ashamed to acknowledge that my own world history textbook (which does pay considerable attention to the role of earlier pandemics) omits the 1918-1919 one in each of its five editions. I’ve no doubt, though, that it will be incorporated into the sixth edition, and that it will also be given added space in the next round of U.S. history textbooks.

Which might suggest that generations of textbooks missed (or at least significantly underplayed) the import of the 1918-1919 pandemic. But maybe history textbooks writers didn’t get it wrong? Disruptive and tragic as the episode was, it did not end up upending societies and economies in the U.S. and around the world. In that sense, Warren Harding’s campaign slogan in the presidential election a century ago calling for a “return to normalcy” turned out to be prophetic when it came to the pandemic’s wake.

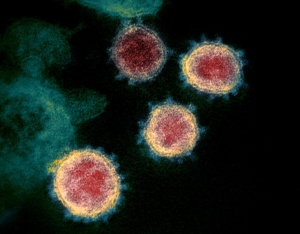

The science and history of Covid-19 by Soraya de Chadarevian

The science and history of Covid-19

The public health measures put in place in many countries around the world in the first phase of the response to the current Covid-19 pandemic — the closing of borders, social distancing, quarantine, isolation, hand-washing and the wearing of homemade masks— seem surprisingly traditional and low-tech. Yet a plethora of cutting-edge scientific approaches accompanies these same measures. Some of these techniques derive from the study of other recent epidemics and pandemics. Others are being corralled from independent investigations and a wide variety of scientific and clinical fields by a myriad of public and private, individual, national and international initiatives. The “curves” that the public health measures aim to “flatten” are the result of internationally shared and pooled data and sophisticated modeling tools. Fast genomic sequencing techniques are deployed to test for the virus and to track its trajectory and evolution. New structural biology techniques like cryo-electron microscopy are put to work to determine the 3D molecular structure of the virus, understand the mechanism of its action and design tools to interfere with its functions. The list continues. And there is still much to understand.

This transmission electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2—also known as 2019-nCoV, the virus that causes COVID-19—isolated from a patient in the U.S. Credit: NIAID-RML

Yet this should not fool us into thinking that pandemics are biological events and that science will or can decide their outcome. Pandemics follow complex historical trajectories and even if politicians vow to “follow the science,” in the end decisions remain political and moral. The virus, far from being non-discriminatory, strikes some people harder than others for a myriad of social as well as biological reasons and political action must mitigate these effects. Science, which is itself a complex social endeavor, can, and hopefully will play its part in shaping the course of this pandemic and in pointing the way to prevent future ones. But this will require radical rethinking and courageous political action.