About Her Meeting

Madina’s Report

History, Policy, and Politics at the UNESCO

On November 23-24, 2017, I attended a meeting at UNESCO’s Paris headquarters, thanks to a joint grant from the UCLA Luskin Center and the Department of History. UNESCO is the body of the United Nations Organization (UN) devoted to education, the natural and social sciences, culture, and communication. The meeting attendees were all academics, either holders of UNESCO-sponsored Chairs in their respective universities or representatives from research institutes and centers affiliated with the organization. All were specializing in topics falling under the scope of UNESCO’s Culture Sector. One of the focal points of the meeting was UNESCO’s current efforts to use cultural and historical heritage preservation as a tool to implement development policy, which resonated with my research in Mali. Additionally, several informal conversations revolved around the upcoming withdrawal of the United States from the organization.

Using Historical Research to Inform Development Policy

In 2015, the UN member States ratified a declaration entitled Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The signatories each pledged to work towards the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in their respective countries. The SDGs are a list of 17 actionable items to be achieved, through policy, by 2030. They include: Climate Action; Decent Work and Economic Growth; Zero Hunger; Reduced Inequalities; etc.

UNESCO believes the work of historians and other scholars is crucial in helping countries implement the SDGs. At the Paris November meeting, Francesco Bandarin, UNESCO Assistant-Director General for Culture, and Jyoti Hosagrahar, head of the Division for Creativity, enjoined academics to keep sharing with the organization research that could help governments better integrate issues pertaining to cultural and historical heritage preservation into their economic development strategies. In short: humanistic and social science research should be part of the policy-making processes of governments seeking to create employment, carry out industrialization projects, attract investments, foster business ventures, etc.

Among the academics in attendance, whose input the organization relies on, were a cultural historian studying theater in Brazil; a Chinese historian and curator recording, preserving, and promoting the industrial heritage of the city of Wuhan; and a number of architects, urban planners, and art historians working on the conservation of historical sites and monuments in their respective countries. Dr. Hosagrahar urged all scholars to consider submitting relevant work to UNESCO, for potential publication and dissemination to the general public and policy-makers. Interested researchers, including graduate students, may reach out to the Division for Creativity.

Rapa Nui National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

© The TerraMar Project

In Mali, where I conduct work, historians have a role to play in critiquing and informing policy-making. Mali, along with the broader Sahel-Sahara area of Africa, has since the 1960s been a site of sustained —though largely ineffective— policy-making from local governments and international organizations, mostly in the areas of economic development and conflict resolution. Yet, many issues these policies target should be framed and understood within their historical context. For instance, the recent publication of a widely shared video-clip showing the auctioning of Black African migrants in a Libyan slave market revived calls for development policies aimed at curbing migration, in order to prevent enslavement and death in the Sahara. Yet, the selling and enslaving of humans in the Sahara is a centuries-old practice, which cannot be tackled solely in the context of South-North migrations. It is crucial that more historians keep speaking out about this practice, as Mauritanian anti-slavery activist Biram Dah Abeid recently did (see also Malian anthropologist Naffet Kéïta’s book L’Esclavage au Mali.)

Politicizing History?

While at UNESCO, I also sought to better understand recent events that have highlighted the deep intertwining of history, policy, and politics that the organization embodies, particularly through the work of the World Heritage Committee. On October 12, 2017, the United States took the unilateral decision to withdraw from UNESCO, effective December 31, 2018, citing “concerns with mounting arrears at UNESCO, the need for fundamental reform in the organization, and continuing anti-Israel bias.” This announcement happened in the wake of the inscription of Hebron/Al-Khalil Old Town as a Palestinian World Heritage site, during the 41st session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee held a few months prior, in July. Did the treatment of a historical site truly determine the United States’ financial and diplomatic policies?

It likely did not. During informal conversations at the meeting, many opined that the United States merely utilized this issue as a pretext to justify their isolationism and lack of interest in allocating money to multilateral diplomacy. As such, the upcoming Trump administration’s withdrawal from UNESCO is a coherent follow-up to the Obama-era decision to stop honoring the country’s dues to the organization —following Palestine’s formal induction as a member State in 2011. Since then, UNESCO has been operating under a considerable strain, having had 22% of its budget cut off. In 1983 already, under the Reagan administration, the United States had left the organization, only to announce their return around the first anniversary of 9/11 in a bid, some have argued, to gain international support for the Bush-era wars.

Boasting National Histories

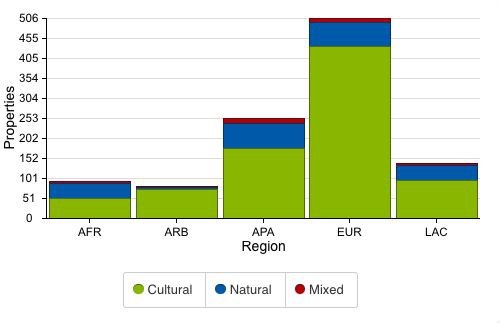

Source: World Heritage List Statistics

As this example shows, World Heritage properties are sites of politics at least as much as they are sites of history. As of today, the UNESCO World Heritage List comprises 1073 natural and/or cultural properties from 167 countries, including Machu Picchu, Timbuktu, Mount Huangshan, the Cathedral of Notre Dame, Chaco Culture, etc. All these properties, according to UNESCO’s criteria, hold Outstanding Universal Value in showcasing nature’s beauty and human creativity, throughout history. Unfortunately, the current geographical repartition of the sites fails to accurately portray the wealth and diversity of natural and cultural heritage in all parts of the world. Rather, it reflects the disparities in economic resources and diplomatic leverage countries are able to devote to heritage preservation. Indeed, while about half of the inscribed properties are located in Europe and North America, Africa is home to less than 9% of those. This does little to counter the commonly-held assumption that Africa has historically neither been home to influential civilizations nor produced intellectual and artistic innovations, which historians of Africa find themselves having to regularly rebut.

At the Paris meeting, Mechtild Rössler, head of the World Heritage Centre, lamented that some States were overly dedicated to inscribing new properties on the list as a matter of prestige, and pointed out that the Centre was struggling to process the continuous flow of applications for inscriptions. Rather, Dr. Rössler stressed, countries should devote time and resources to work on the safeguarding of already inscribed sites, especially those endangered by conflicts or climate change, such as the cities of Aleppo or Timbuktu.

“We must be optimistic.”

This was Michael Turner’s response to my skepticism regarding the future of the organization, as we talked on the last day of the meeting. Prof. Turner holds the UNESCO Chair in Urban Design and Conservation Studies at the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem and specializes in architecture, conservation, urban design and historic cities. He pointed me to some of the organization’s founding documents. Its 1945 Constitution, for instance, argues the need for a UN agency solely dedicated to education, science and culture, based on the idea that “since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defenses of peace must be constructed.” Reading these words, I mentally wandered away from UNESCO, and back to Mali: I was reminded of Boukary Konaté. Until his passing this past September, Mr. Konaté, an educator and language teacher, tirelessly collected, digitalized, translated and spread Malian rural traditions and oral histories that would have otherwise remained little accessible, or might have been lost. He set out to do so on his own, with few resources and no compensation. Optimism is warranted as long as academics, historians, and UNESCO, keep striving to do work emulating that of Mr. Konaté and others like him.

Madina Thiam is a doctoral student in History at UCLA, and co-editor-in-chief of Ufahamu: a Journal of African History. She represented Mali at the 2017 UNESCO World Heritage Young Professionals Forum.