Short Takes by UCLA Historians: Are we in a Fascist Age?

These short takes are part of a series of short and diverse reflections by historians on our current moment. The following “short takes” offer historical perspective on the recent insurrection on the U.S. Capitol, Trumpism, and the future of democracy in the United States.

Click here to read our previous Short Takes reflecting on the COVID-19 crisis.

Trump and the Problem of Truth in Democracy by Andrew Apter

As someone who works in Nigeria and combines history and political anthropology in my research, I have personally experienced two coups d’état (the first in 1983, the second in 1992) following failed elections with the smug confidence that once I returned to the United States, I would be safe from such unbridled madness. That is, until Trump and the Trumpism that he unleashed. Democracy in postcolonial Africa is both recent and frail. Democracy in America is built into our nation’s DNA. We don’t need Alexis de Tocqueville to remind us that our culture of democracy, enshrined in our constitution, is protected by our legal system and institutionalized in our civil society.

So how has Donald Trump managed to trample on our political norms, break the political contract with impunity, and create a delusional narrative of electoral theft? How has he so effectively undermined the credibility of our electoral process?

I can’t answer this question in a few hundred words, but I can highlight two related problems that conventional historians and political scientists overlook, and which remain central to modern social contract theory. The first concerns an adequate theory of reference for a political philosophy of democratic representation. How do we guarantee a binding relationship between the national vote and the will of the people; between the “number” of votes cast and the constituencies who voted? Here we need criteria to establish that the vote corresponds to the will of the people. The second is an adequate theory of meaning and discourse, in that we agree on the meanings of words, sentences and the social conditions of mutual intelligibility that establish the “truth” of our referential claims. Assertions and allegations of electoral fraud must be connected to mutually intelligible referential evidence rather than the “alternative facts” of baseless claims.

But not for Trump and his “stop the steal” devotees. Somehow Trump has undermined not only trust in government and the established media, but in the very semantics of democratic representability. He has severed the truth-claims of his discourse from the juridical conditions of its verification. These are the techniques used by Ibrahim Babangida in Nigeria, Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe, and Yoweri Museveni in Uganda to quash the opposition and remain in power, particularly when the opposition would otherwise win. Thus far, the only difference between Donald Trump and his designated “shithole country” brethren is that our courts have remained relatively autonomous, ![Military Rule in Nigeria - History & Impacts [Explained] - Oasdom](https://www.oasdom.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Oasdom.com-Military-rule-in-Nigeria-First-coup-auiyi-ironsi.jpg) notwithstanding the proliferation of Trump appointees. That Senators Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz in the Senate, and over a hundred representatives in the House, persisted in challenging Biden’s electoral votes after the January 6 assault on the Capitol highlights the extent to which the meanings of words and their reference to the 2020 presidential election have become unhinged from their epistemological and institutional moorings. We may have won the battle but we still could lose the war. Trust in words and numbers matters, as do the social conditions of their ratification.

notwithstanding the proliferation of Trump appointees. That Senators Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz in the Senate, and over a hundred representatives in the House, persisted in challenging Biden’s electoral votes after the January 6 assault on the Capitol highlights the extent to which the meanings of words and their reference to the 2020 presidential election have become unhinged from their epistemological and institutional moorings. We may have won the battle but we still could lose the war. Trust in words and numbers matters, as do the social conditions of their ratification.

Andrew Apter, Professor, Departments of History and Anthropology

Interim Director, James S. Coleman African Studies Center

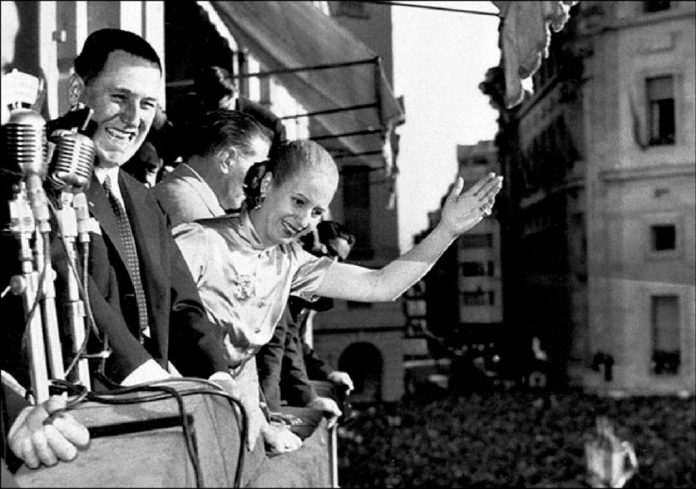

Mobilizational Politics and Populism by Robin Derby

Much political commentary has focused recently on our authoritarian turn, which seeks to explain how Trump has been able to gain a stronghold over political institutions, culminating in what some have termed an attempted coup, but which Latin Americanists would call an “auto golpe” (self coup) as a leader seeks to retain office beyond his term.

But as a Latin Americanist who has long studied authoritarian populism, I have been intently focused on another aspect of this moment – the way in which emerging media has enabled a mobilizational politics with a powerfully emotive resonance for his base.

The classic Latin American populists of the 1940s used new media to reach out to the masses in a far more direct fashion than traditional liberals and their newspapers, and in doing so they invented a far more mobilizational style of politics. Juan Perón, for example, and his wife Eva drew upon radio as a medium and the language of melodrama and nostalgia that saturated radio soap operas and Tangos of Depression-era Argentina to establish a much more powerfully emotive political rhetoric than staid traditional liberals; one that drew upon what historian Matt Karush has termed a “binary moralism” which divided the world into starkly opposed categories of good versus bad, weak versus strong, and us versus them (The New Cultural History of Peronism, 25). In this way it developed a powerful new emotional register, a heretical inversion of social hierarchy and a broader anti-intellectualism which hailed the working class into the streets and into political life for the first time.

The classic Latin American populists of the 1940s used new media to reach out to the masses in a far more direct fashion than traditional liberals and their newspapers, and in doing so they invented a far more mobilizational style of politics. Juan Perón, for example, and his wife Eva drew upon radio as a medium and the language of melodrama and nostalgia that saturated radio soap operas and Tangos of Depression-era Argentina to establish a much more powerfully emotive political rhetoric than staid traditional liberals; one that drew upon what historian Matt Karush has termed a “binary moralism” which divided the world into starkly opposed categories of good versus bad, weak versus strong, and us versus them (The New Cultural History of Peronism, 25). In this way it developed a powerful new emotional register, a heretical inversion of social hierarchy and a broader anti-intellectualism which hailed the working class into the streets and into political life for the first time.

Our equivalent is of course the hyperbolic language of reality television, which arose in the 1990s and conjures a world divided into winners and losers. I had been focused until this week on how Twitter has provided a parallel media form which Trump has used effectively to hail his base directly without mediation, one which has carried the mobilizational tactics of the mass rally into his followers’ everyday lives and conjured a sense of urgent intimacy with his supporters which have enabled Trump’s followers to feel heard.

But Russ Douthat invoked another media form that also seems to have shaped the January 6th insurgency – video games – when he described the participants as wrapped in an “immersive narrative” of electoral fraud, one which cast them as righteous avenging warriors, as he put it as “actors in a world historical drama, saviors or re-founders of the American Republic” (“How Trump made the Fantasy Real,” The New York Times Jan. 9, 2021). The trouble with this kind of populist identification is that its power is emotive rather than rational, which is why it cannot be easily dissuaded by facts and reasoning. Let’s hope that we do not become another Argentina where until today Peronism continues to dominate politics.

Robin Derby, Associate Professor, Dept. of History, UCLA

The March on Washington by Brian J. Griffith

A Sign at the Capitol Insurrection Depicting Trump as an Anti-Marxist “Braveheart” Freedom Fighter. Photo by Dave Weigel/The Washington Post.

The armed insurrection at the Capitol on January 6, 2021 surprised, and undoubtedly horrified, many Americans. For historians of twentieth century authoritarianism, however, the attempted violent overthrow of American democracy was merely an all-too-predictable outcome of the charismatic cult of personality and fascistic propaganda campaigns unleashed by Donald J. Trump over the past four years.

In spite of the relatively unified voice among scholars of authoritarianism in warning the American people about the dangers posed by the MAGA movement to the maintenance of democracy in the United States (US),[1] scholars of Fascism and Nazism specifically have remained largely divided on whether or not Trumpism constitutes a peculiarly American form of “generic fascism” (or the common ideological components shared by all fascistic movements).

One of the underlying problems with this lack of consensus, of course, stems from the fact that, unlike Communism and Capitalism, Fascism has no singular founding document, or even corpus of documents, which has greatly complicated the development of a working definition of what is and is not “fascist.” As a result, there are numerous competing interpretations of Fascism.

While some have adopted a Marxist, or “materialist,” perspective, choosing to view Fascism as a “terrorist dictatorship” consisting of “the most reactionary, most chauvinistic, most imperialist elements of finance capital,”[2] to quote Palmiro Togliatti, the second Chairman after Antonio Gramsci of the Communist Party of Italy, others have opted to interpret Fascism as a revolutionary expression of “palingenetic ultra-nationalism” whose “raw materials,” to quote Roger Griffin, were “militarism, racism, charismatic leadership, populist nationalism, fears that the nation or civilization as a whole was being undermined by the forces of decadence, … and longings for a new era to begin.”[3]

Robert O. Paxton, on the other hand, who has long since opposed labeling Trump a “fascist,” has adopted the interpretive position that “what fascists did tells us at least as much as what they said,”[4] urging scholars to look beyond these movements’ bombastic rhetoric and political symbolism and focus more closely on their paramilitary violence and their conspiracies against the democracies they undermined and, in many cases, toppled.

Putting these ongoing interpretive and methodological debates aside, however, a number of loose comparisons can indeed be made between historical fascisms and Trump’s MAGA movement.

Much like Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler before him, for instance, Trump has carefully cultivated a charismatic relationship with his followers by promising to put “America First”—a reference to the 1940s pro-Nazi, anti-interventionist movement in the US by the same name—and “Make America Great Again”—a plausibly deniable nod to notions of regenerative ultra-nationalism.

What’s more, he has cynically deployed his Leader cult relationship with his followers towards inflicting fascistic, purificatory violence against his “enemies”—a campaign which has included left-wingers, establishment politicians, the press, and now the country’s democratic institutions.

Having perpetrated a Hitlerian “Big Lie” with respect to the outcome of last year’s general election—an untruth so colossal in scope and scale, to quote directly from Mein Kampf, that “the broad masses of a nation” are “easily corrupted”—Trump has successfully established an alternative reality for his followers, in which he is the hero, the patriot, or the victim, and everyone else is a “traitor,” a “communist,” or a “tyrant.”

Highlighting these fascistic qualities of Trumpism and the MAGA movement, one Trumpist published the following remarks in a post-insurrection “parley” on Parler: “what needs to happen is leftist commie democrat traitor politician [sic] kids and grandkids need to be burned alive or thrown into wood chippers in front of them,” for only when “democrats see Americans murdering their wives kids parents grandparents etc.” will they realize that “[t]here’s 50 million fighting aged male Trump MAGA supporters” who are fully prepared to “do what is needed to save America from Marxist commie filth.”[5]

Taken together, all of this has deeply alarmed Americans and foreign observers alike.

Last November, just as Americans were going to the polls to vote in the 2020 general election, I along with over 200 other scholars of authoritarianism co-authored a letter of concern which explicitly warned that, given our (inter)national circumstances, “the temptation to take refuge in a figure of arrogant strength is now greater than ever.”[6]

Among the more prominent signatories was Paxton, who recently published an op-ed in Newsweek addressing the Capitol siege: “I’ve resisted for a long time applying the fascist label to Donald J. Trump,” Paxton explains, adding that: “Trump’s incitement of the invasion of the Capitol on January 6, 2021 removes my objection to the fascist label.”[7]

Closely resembling Mussolini’s March on Rome and Hitler’s (ultimately unsuccessful) Beer Hall Putsch, the January 6th attack against our country’s hallowed peaceful transfer of power between incumbent and incoming administrations places Trumpism and the MAGA movement squarely within what might be referred to as a fascistic political spectrum. Indeed, given everything we know about Trump, the insurrection at the Capitol might very well be referred to by future historians of twenty-first century America as our country’s March on Washington.

[1] See, for instance, the Twitter profiles of scholars such as Timothy Snyder (@TimothyDSnyder), Ruth Ben-Ghiat (@RuthBenGhiat), and Federico Finchelstein (@FinchelsteinF), among many others.

[2] Palmiro Togliatti, Lectures on Fascism (New York: International Publishers Co., Inc., 1976), p. 1.

[3] Roger Griffin, The Nature of Fascism (New York: Routledge, 1993), p. 38.

[4] Robert O. Paxton, The Anatomy of Fascism (New York: Vintage Books, 2004), p. 10.

[5] JuarezTX, Parler (January 9, 2021), a screenshot for which is available at: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/ErY6yY1XAAIm3u5?format=jpg&name=large.

[6] Editorial Board of the New Fascism Syllabus, “How to Keep the Lights on in Democracies: An Open Letter of Concern by Scholars of Authoritarianism,” The New Fascism Syllabus (October 31, 2020), available at: http://www.newfascismsyllabus.com/news-and-announcements/an-open-letter-of-concern-by-scholars-of-authoritarianism/.

[7] Robert O. Paxton, “I’ve Hesitated to Call Donald Trump a Fascist. Until Now,” Newsweek (January 11, 2021), available at: https://www.newsweek.com/robert-paxton-trump-fascist-1560652.

Dr. Brian J Griffith

Historian of Modern Europe/Fascist Italy

Postdoctoral Scholar in European History, UCLA

A Divided America by Kevin Y. Kim

Trumpism, we often hear, is neo-fascism. With its potent mix of herrenvolk democracy and authoritarian politics, Trumpism certainly bears parallels with 1930s-era European fascism. Born of socioeconomic grievances and propelled by ethnoracial politics, Trumpism, like Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers’ Party (or Nazism, as it’s popularly known), relies on a leader-centered cult of personality to promote a far-right mass politics. In the sacralized name of the “nation,” Trumpism, like Nazism, has repressed minorities, coerced private interests, and trampled on basic constitutional safeguards in revanchist pursuit of a fascist-like myth: an ideologically pure and materially prosperous vaterland. Like the Nazi German swastika, “Make America Great Again” hats symbolize fervent membership in a tribalistic polity where dissenters and political opponents are deemed traitors to the “nation.”

But while history instructs, it can also mislead. Despite these parallels with fascism, Trumpism retains its proponents’ decidedly non-fascistic tendencies. Central state planning, the engine of fascism, under Trump has been ad hoc and slipshod, at best. Rather than serving as handmaidens to the state, most major U.S. businesses and private interests, well before the recent Capitol Hill riots, maintained some distance from Trumpism. Despite Trump’s constant assaults on his political opponents, the United States is far from single-party rule. As with Trumpism’s means, so with its ends. Rather than seeking global military conquest, Trumpism eyes more traditional goals which evoke a nostalgic U.S. past: U.S.-dominated treaties and alliances, not multilateral arrangements in a global society of equal partners; crony capitalism, not fascism’s systematic state-led capitalism; civil and human rights rollbacks and immigration restriction, rather than full-blown ethnic cleansing and settler colonialism. Instead of aggressively expanding U.S. territory and power, Trumpism has sought to consolidate, redeploy, and redistribute U.S. power and resources in ways defined by its “America First” constituencies. In short, Trumpism stands for a different, uniquely U.S. libertarian myth: an exceptionalist nation, standing apart from other nations, the proverbial city on a hill pursuing its interests with little regard for others.

This month’s inauguration of a new U.S. president, Joseph Biden, confirms these differences. For now, Trumpism has evoked enough public resistance to keep the former at bay. Such resistance, however, should not lead to complacency. What the future holds, particularly as Biden embraces old formulas as well as some new, untried ones, is uncertain. Historians are better at predicting the past than the future. However, if we are to bring history to bear on today’s divisive, increasingly desperate, political atmosphere, it would be better if we did not try to tag, in moralizing fashion, fascism and Trumpism as twin evils. Rather than seeing either as sui generis, we would do better placing them on a spectrum of sociopolitical possibility arising from shared contemporary problems: inequality, racism, geopolitics, and, not least, the capacity of democracy to respond to modern society’s mounting domestic and global challenges. Not a fascist America, but a divided America—along multiple fissures besides fascism and anti-fascism—seems here to stay. Addressing these divisions will require what history teaches us: grasping the complex, interrelated causes and contingencies behind our politics and policies. Only by unraveling and debating these tangled knots of our history can historians, citizens, and policymakers begin to find a way forward.

Familiar Signs of Fascism by David N. Myers

The armed insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6 was shocking both because it was so foreign and yet so familiar. Never before had the seat of American power been attacked in such a brazenly violent way. But then again the sight of an angry mob waving a Confederate flag through the halls of Congress—and erecting a gallows with a noose just outside—is hardly an alien image in American public memory.

This kind of rage-filled violence, at once directed at and yet instigated by the political establishment, calls to mind a different historical setting at a remove from American shores. In the aftermath of the First World War, there was an explosive clash between forces of revolutionary, messianic hope and reactionary nationalist despair in the nascent Weimar Republic. Following the barbarizing effects of the War, Germans across the political spectrum increasingly expressed their disagreement in violence. Hundreds of political activists and leaders were killed in the spasms of violence shortly, including the prominent Communists Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, and Kurt Eisner. An especially incendiary catalyst was the Freikorps, consisting of recently demobilized veterans organized into p

aramilitary groups. Outraged by the perceived slight to national honor imposed by the war’s winners, Freikorps members were used by the new government to neutralize political enemies (such as Luxemburg and Liebknecht), while also acting against the interests of the government in support of their own anti-democratic agenda.

aramilitary groups. Outraged by the perceived slight to national honor imposed by the war’s winners, Freikorps members were used by the new government to neutralize political enemies (such as Luxemburg and Liebknecht), while also acting against the interests of the government in support of their own anti-democratic agenda.

The specter of self-identified military veterans and law enforcement officers participating in the Capitol insurrection of January 6 triggers memory of the Freikorps, as well of Adolf Hitler and his fellow demobilized soldiers in the Nazi Sturmabteilung, who attempted their beer hall Putsch in Munich in October 1923. So too the behavior of an egomaniacal and charismatic autocrat, abetted by a mix of political insiders and external disrupters, recalls the fascist and totalitarian sensibilities that took rise in Interwar Europe. Scholars including Ruth Ben Ghiat, Samuel Moyn, Jason Stanley, and perhaps most notably, Timothy Snyder have passionately debated how fitting the term “fascism” is in describing Donald Trump, his political enablers, and his base of supporters.

To be sure, there are clear differences between today’s world and the Nazi era, and there are always risks of imprecision in proposing historical analogies. But we ignore clear warning signs—a cult of personality, the vilification of political enemies, the routinization of violence as a means of political expression, and the refusal of one side to play by the rules of the democratic game—at our own great risk. History may not be repeating or even rhyming, but it is unmistakably calling out to us.

David N. Myers holds the Sady and Ludwig Kahn Chair in the UCLA History Department and directs the UCLA Luskin Center for History and Policy.